Vietnam veteran’s compelling story shared with Quinnipiac community on Veterans Day

November 12, 2025

November 12, 2025

In late September of 1967, less than a year after enlisting with the U.S. Marines at age 21, PFC Mannion was sent to Khe Sanh, Vietnam.

By late December 1967, Mannion, now a corporal, was dug into a bunker on Hill 861 with Kilo Company, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marine Regiment. Mannion was an Artillery Forward Observer for the regiment. The hill was key factor in the battle for Khe Sanh, a strategic location held by the U.S. military just south of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) separating North and South Vietnam. Many of Mannion’s friends were killed or wounded as the battalion held the hill during a 77-day siege.

“For people that know their history, they dropped more bombs, tonnage-wise, in 77 days at Khe Sahn than they did in all of Europe in World War II,” said Mannion.

When he arrived in Khe Sahn to begin his 13-month tour, it was a place Mannion had already heard about.

“Khe Sanh had been famous in the news during the spring of ’67 when I was in boot camp, for what were called The Hill Fights, where a lot of Marines were killed and all kinds of NVA [North Vietnamese Army] were killed fighting over three hills,” said Mannion. “I came out of my tent one morning when it wasn’t foggy, and somebody said to me, ‘Do you see that bump over there? That’s Hill 861,’” said Mannion.

The hill been secured by American forces in May of 1967 following heavy battles. To see it was the equivalent of someone pointing out the Alamo or Omaha Beach, said Mannion.

“This was so famous in Marine Corps history,” said Mannion.

Using the Instamatic camera he bought at the Hamden Plaza before leaving for boot camp, Mannion took a photo of the hill. It was one of many in-country wartime photos taken by Mannion and sent home to be developed -- photos he wouldn’t see until after he returned home. Mannion shared many of these personal photos during his presentation in The SITE auditorium on November 11.

“I took that picture thinking, ‘Wow, I’m so close to this famous hill,” Mannion said. “I didn’t know it then. I didn’t know it until the day before Christmas in ’67, when we were told we were going there the day after Christmas. And when the fighting broke out in January, 28 of my friends were killed up there. Most of the people I know who survived were wounded. And there isn’t a day in my life that goes by that I don’t think about that hill.”

On January 20, 1968, NVA forces attacked Hill 861 as part of a horrendous, multipronged assault. Mannion shared a photo of an area demolished by a bomb attack that night.

“What you don’t see is the first NVA soldier who got inside the wire on January 20 of ’68 with an assassin charge on his back and blew himself up,” said Mannion.

The fighting continued for nearly four months. Mannion remained on Hill 861 with his battalion until it the order finally came to withdraw in April,1968. The Purple Heart recipient was wounded twice.

“I owe my life to corpsmen,” he said of the Marines’ medical personnel. “They do an unbelievable job.”

Mannion also described another close call during his tour, prior to digging in on Hill 861.

“We were on a ridgeline, running ambushes at night and patrols in the morning,” said Mannion, sharing a picture of the foxholes he and his buddy, a radioman, had dug for shelter.

“One afternoon we came back from patrol, and all of the sudden, -- boom! Boom! Just like fireworks, those big shells that kick way up before they drop back down on the Fourth of July.”

Under intense mortar fire, Mannion and his buddy jumped in their foxholes.

“And then you wait; and it’s terrifying, mainly because you have time to think,” said Mannion.

Between the terrible boom of each mortar launch, Mannion listened and waited an eternity – 12 to 15 seconds – for the shells to hit the ground. One exploded nearly on top of him.

“The round hit right between our two foxholes,” said Mannion. “When you are in that hole, if the round lands in the foxhole you’re in, you’re a dead person. It doesn’t matter what color you are, what religion you believe in, whether you hate sports, love books -- it doesn’t matter. If the round lands in the hole you’re in, you’re dead. And you have to wait that 12 seconds for it to happen. It’s terrifying.”

From the day of that attack, Mannion still has his military-issued towel. It was peppered and shredded with shrapnel holes as it hung on a branch near his foxhole. Mannion held the towel up to show his Quinnipiac audience.

“Every little hole means surgery, and every big hole means you’re dead. I think shrapnel is the biggest cause of death on battle fields. It’s just pieces of metal flying in every direction,” said Mannion.

In 2000, Mannion returned to Vietnam and was able to visit Hill 861 with a group of veterans and friends. While he was there, he found the site of his old bunker – the spot where he had called in targets for artillery attacks against the ridgeline where the NVA was entrenched.

He shared photos of the hill as it looked in 1968 and in 2000. Perhaps more startling were the photos Mannion shared which showed how his time in Vietnam had changed him; from a freshly-arrived military member into a war-worn Marine.

“This picture is September 20, ’67. The next picture is April of ’68. Same pose; totally different person,” said Mannion.

To close his presentation, the Vietnam veteran shared a heartwarming family photo of the extended Mannion family today, including the couple’s four children and spouses and their grandchildren.

“This is my family,” said Mannion, holding back tears. “I feel really lucky and privileged to be alive. I always feel for the guys that I knew personally that didn’t come home, who died over there that were good friends of mine; and the 58,000 who never got a chance to have a family.”

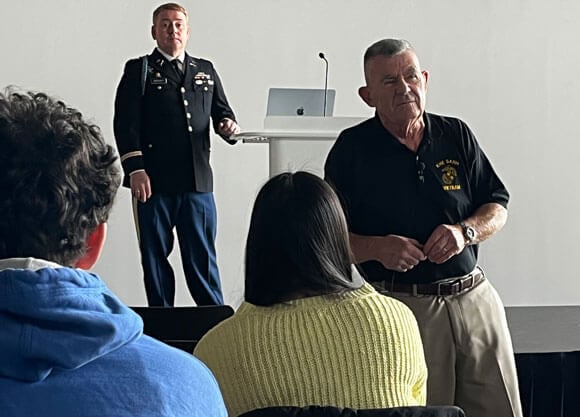

Mannion spoke at Quinnipiac during Common Hour on Veterans Day at the invitation of First-Year Seminar instructor Daniel Geraghty.

“As part of First-Year Seminar, we’re talking about Bitter vs. Better. It’s about getting through trauma and living your life better and not focusing on bitterness. I could not think of anyone in my life that embodies that more than Dennis Mannion,” said Geraghty.

Geraghty wore his dress uniform for the event. He was active duty as a U.S. Army Ranger with the 10th Mountain Division and served with the National Guard based in New York and Connecticut. Geraghty met Mannion when he first started teaching high school English.

“Dennis was a guest of a teacher and came to speak for Memorial Day. I met him and we’ve been friends ever since. He’s done so much for me in my life and he’s the kind of guy that if you give him a call, he’ll be there,” said Geraghty.

Mannion returned home from Vietnam in October of 1968 and was honorably discharged with the rank of Seargent in December of 1969. He taught English and coached football at Sheehan High School in Wallingford for 30 years.

On November 11, Mannion received a standing ovation from his Quinnipiac audience. He stayed after his talk to meet with students, faculty and staff who came up to thank him personally for his service.

Quinnipiac Today is your source for what's happening throughout #BobcatNation. Sign up for our weekly email newsletter to be among the first to know about news, events and members of our Bobcat family who are making a positive difference in our world.

Sign Up Now