School of Law’s ‘Executive Orders 101’ answers timely questions for greater Quinnipiac community

March 05, 2025

March 05, 2025

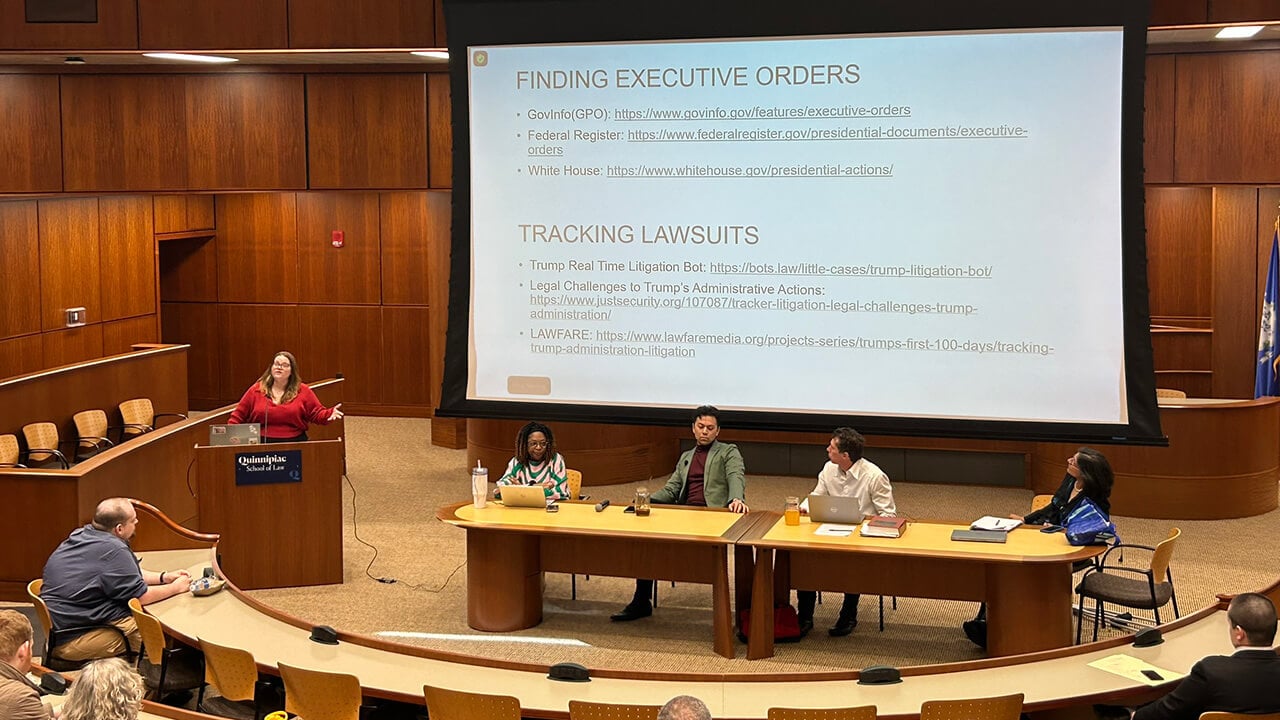

The February 25 panel event was moderated and organized by Jordan Jefferson, director of the Lynne L. Pantalena Law Library and associate professor of law, and co-sponsored by the Office of the Provost.

“Executive orders have become a focal point of discussion in the current political landscape, particularly under the second Trump administration. These presidential directives have far-reaching implications for policy, agency operations and everyday life in the United States,” said Jefferson.

Jefferson said the panel’s goal was to explore the nature and impact of executive orders and consider how they interact with other branches of government and their role in shaping the direction of the country under the current administration.

Panelists were Judge Angela C. Robinson (Ret.) a law professor and a Waring and Carmen Partridge Faculty Fellow; clinical law professor Sheila Hayre, who teaches immigration law; Assistant Law Professor Wayne Unger; and School of Law Associate Dean for Student Success and Law Professor Kevin Barry.

In part, Barry pointed to two historic presidential executive orders: Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, and Franklin Roosevelt’s order requiring the relocation and internment of Japanese Americans.

“Both of these orders mark an extraordinary use of executive power, and all would concede history has judged these two orders very differently. So how will history judge the orders we are seeing now?” Barry asked.

The president has the constitutional power to direct agencies to act in order to implement policy goals.

However, Barry said, “…there are some agencies that don’t have to listen to the president. They are called independent agencies.”

Such independent federal agencies include, but are not limited to, the Central Intelligence Agency, Federal Communications Commission, Federal Elections Commission, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Selective Service System, and Social Security Administration. They are generally led by multiple appointees, such as a commission, and serve staggered terms of several years which can continue under new administrations.

“And here’s the important part: They are only removeable for cause,” said Barry. “So basically, it’s hard for a president to get rid of these independent agency members. The president can’t tell them what to do.”

Barry also cited precedent created by a 1935 Supreme Court decision (Humphrey's Executor v. United States) finding Congress can limit the president’s removal of agency officials. However, the court left open the possibility that Congress may not be able to limit the president in all circumstances, particularly where it impedes the president’s ability to perform his constitutional duties.

“That will be where the current administration is going to press,” said Barry.

The panel also discussed how executive orders have two sources of authority: the power directly granted to the president under the Constitution, and the authorization of Congress.

“If the executive order doesn’t pass constitutional muster, it is invalid,” said Hayre.

Hayre also shared her thesis that the issue at hand is not about the number of executive orders, but about the abdication of power by Congress through action or inaction; combined with the immediate effect of the messaging being sent by executive orders which are obviously constitutionally invalid, such as the January 20 executive order targeting birthright citizenship.

The U.S. Supreme court established the principle of birthright citizenship with its landmark decision in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), finding children born in America are citizens, regardless of their parents' immigration status. The decision is based on the 14th Amendment, Section 1 “Citizenship Clause” language which states “…all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and the state where they reside.”

However, some legal scholars may argue the birthright citizenship executive order could be enacted by Congress by targeting the verbiage, “…subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” Hayre said.

“But nobody says Trump can do this with an executive order. And this is where we head into the chilling effects,” Hayre said.

Hayre also emphasized the temporary nature of executive orders, which can be invalidated by presidential action (revocation or amendment by current or future presidents), judicial action, or congressional action to enact a valid statue reversing or overriding an executive order.

Unger said many Americans are essentially asking “Why?”

“Why these executive orders, why this volume, why is the Trump administration issuing executive orders that are blatantly unconstitutional and unlawful? The thing is, the judicial system, whether it’s state or federal, is reactive in nature. A case needs to be brought to it before it can act. A court cannot rule something is unconstitutional unless someone brings a case to the court,” said Unger.

Once executive orders are signed, cases can begin to work their way through the court system and may rise all the way to the Supreme Court. Depending on the makeup of the justices, new precedent may be set, such as the 2022 overturn of Roe v. Wade with the Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization.

“Roe could not be overturned, no matter how much any justice wanted it to be overturned, until the right case was brought before the court, and they had five votes. We will see at some point the birthright citizenship order work its way up to the Supreme Court, and we may have new precedent to follow, because the court can overturn Wong Kim Ark,” said Unger.

In such cases, the hands of Congress are essentially tied, Unger said. Amending the federal constitution is an overwhelmingly difficult task, needing passage by both chambers and ratification by three-quarters of the country’s state legislatures.

Provost Debra Liebowitz said she was glad to see so many students, faculty and staff from across the university attend the panel discussion.

“This is obviously a topic of interest to all of us. Whether you’re a political scientist like me and you’ve thought about this before, or executive orders have suddenly come into your consciousness, this is important and timely,” Liebowitz said.

Quinnipiac Today is your source for what's happening throughout #BobcatNation. Sign up for our weekly email newsletter to be among the first to know about news, events and members of our Bobcat family who are making a positive difference in our world.

Sign Up Now